Publicité

Demographics

Why Immigration is no magic bullet

Par

Partager cet article

Demographics

Why Immigration is no magic bullet

While for years the government has attempted to entice the Mauritian diaspora to come back to work in Mauritius, the result has been the opposite.

The Finance Minister Renganaden Padayachy has urged the private sector to boost salaries to make itself more attractive and stem the brain drain problem. Here is why Mauritius’ shrinking demographic is making this reimagining necessary. And why relying on immigration to resolve the problem is not a real long-term solution for Mauritius.

1. The private sector’s problem

Finance Minister Renganaden Padayachy has suggested that the private sector in Mauritius regularly reviews salaries to make itself more attractive and help stem the brain drain problem in Mauritius. This was during the seventh meeting of the Public-Private Joint Committee on September 1. Padayachy took the example of the financial sector and tourism to highlight how Mauritian business is no longer able to keep talent.

The roots of this problem go back some time. A couple of decades ago, the idea was that while public sector jobs offered perks and job security, the private sector paid better. In 1994 the government started the Pay Research Bureau (PRB) system to keep public sector salaries in step with private sector pay. However, by the mid-2000s, this balance broke down. Battered by the end of trade agreements and the shrinking of mass-employing industries such as sugar and textiles, while pay in the public sector continued to grow because of the PRB system, salary growth in the private sector lagged far behind. “The salary structure is the other way around now,” says economist Vinaye Ancharaz, “It was a bit brave of the minister to bring this up. At the moment, what you have is the public sector lavished with all sorts of non-monetary perks, wage growth and job security while the private sector doesn’t. There is a huge divide now between workers in both sectors and it’s high time that the private sector acts to rebalance that.” This problem makes itself felt in several ways: first, a clear preference for public sector jobs over private sector ones, and young people prefer to stay out of the job market rather than take up poorly paid private sector work. “How do you explain youth unemployment standing at 23 percent while having to import labour? How is that contradiction to be explained?” asks Ancharaz, “If graduates are offered a minimum wage to start with, they are not going to work for that.”

The other way in which this discontent with private sector pay is making itself felt is emigration. While for years the government has attempted to entice the Mauritian diaspora to come back to work in Mauritius, the result has been the opposite. According to government statistics, since 2012, the rate of young, working-age Mauritians leaving to work and live abroad is estimated to average about 1,800 each year. This is a rate of emigration that in the past has been seen only in times of great political or economic stress in Mauritius, such as during the exodus around the period of Independence in the 1960s or the economic doldrums of the late 1970s, and early 1980s when emigration rates averaged about 2,000 annually. Mauritius Inc. has a serious problem on its hands.

“Our young people have gotten used to a way of life that previous generations who saw hard times did not,” says economist Pierre Dinan. “I accept that the lack of attractive pay in the private sector can be a factor, but is it the only one? Is this also influenced by a lack of fair treatment and equal opportunities here?”

2. The Demographic Decline

The sense of urgency over high emigration and the inability to keep talent in Mauritian business exist because it is taking place in a context of declining demographics.

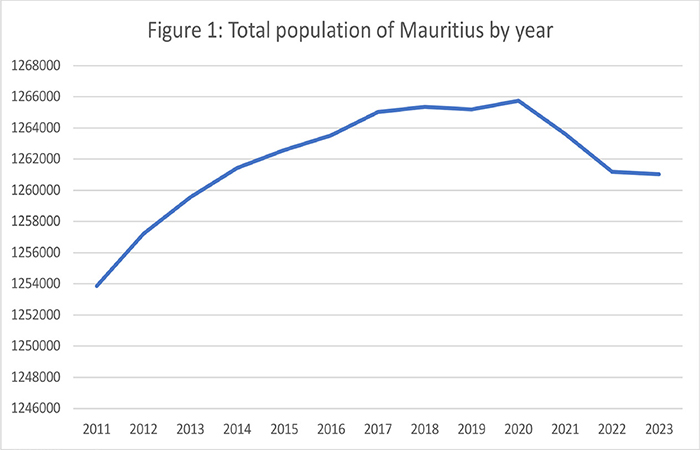

Source: Statistics Mauritius.

Source: Statistics Mauritius.

Just after Independence in 1968, the Mauritian government was convinced that it was facing a Malthusian nightmare. Between the early 1900s and the 1930s, the population remained stable at just under 400,000. However, with the eradication of malaria in 1949, Mauritius saw a demographic boom that doubled its population to over 800,000 by the 1970s. Unable to create jobs for so many young people and the prospect of the limited land and resources being exhausted by an ever-growing population (the “overcrowded barracoon” of V. S. Naipaul), the government turned to a robust program of family planning. It only worked too well; by 1974, the fertility rate had halved from the 4.1 it was before Independence. Government encouragement of family planning, the spread of contraception, greater education and women entering the workforce, all combined to plunge fertility rates to 1.4 today, with Mauritius rivalling the rates of poster countries of demographic collapse such as Poland (1.38) and Japan (1.34).

A collapse in fertility takes a few decades to make itself felt in total population numbers. In Mauritius, this has been seen since 2019-2020 when for the first time the total population has shrunk. And has so each year ever since. (see Figure 1). In 2022, the total number of Mauritians shrunk by 2,692 compared to 2021, and by June this year, the number has gone down by a further 1,482. This is what makes the added problem of the brain drain, young working-age people moving out for greener pastures elsewhere, even more serious.

3. Why Immigration alone won’t work

Part of the reason for the complacency around this demographic problem within Mauritian business is the idea that simply opening Mauritius up to more immigrants would resolve the problem.

In the recent Budget 2023-2024, the government has come up with a raft of new measures to encourage foreigners to come and work in Mauritius, such as making it easier to get occupation permits, registering with professional associations, and opening up more jobs in agriculture and manufacturing. “We have no choice; there is no other alternative. By 2050, our population will be the same as it was in 2000 and by the end of the century, it will dip to 800,000 (the same as the 1970s – ed.) says Ancharaz, with the proviso that a growing proportion of them will be the elderly. Aside from these, the government has also embarked on a modest pro-natalist policy such as offering cash for bigger families and creches for working mothers. “I don’t think these pro-natalist policies will have much of an impact. The problem is a more fundamental one about the cost of living,” he adds. But when it comes to encouraging immigration too, the solution is far from certain.

Firstly, while Mauritius has looked to immigration in the past, it has done so for relatively low-skilled occupations such as sugar cultivation or as labour in textile and seafood processing factories. With agriculture and textiles increasingly making up less of the Mauritian economy, attracting high-skilled immigrants for other more complex sectors is another matter entirely. It is here that Mauritian experience and success are much more limited.

Secondly, the global context today is totally different than it was in the 19th and 20th centuries. Global fertility is collapsing and is poised to shrink to 1.7 by the end of the century, with 183 out of 195 countries unable to maintain stable populations without generous immigration policies. Europe, the US and East Asia are already witnessing demographic declines with countries such as India seeing its fertility rate plummet to 1.99 in 2017-2019 according to its own National Family Health Family Survey. The only part of the world where the demographics are still growing is sub-Saharan Africa (by the end of the century Africa is projected to make up 38 percent of the world’s population), but here too fertility rates are starting to go down and are estimated to reach the bare replacement level by the end of the century.

For Mauritius, this has two major consequences. Firstly, if in the past it could rely on a ready pool of cheap labour elsewhere to step in and work, today that is no longer the case. And shrinking fertility and populations in the developing world that leads to pressures on wage growth within those countries too means that it will become an even more unrealistic strategy as time goes on. In short, simply opening the doors won’t work because there is no global pool of cheap labour anywhere in a world where fertility and demographics are in decline.

Secondly, such a strategy of simply waiting for foreigners to come in for low wages will fail for the same reason that Mauritian business is failing to attract Mauritians themselves. As global demographics go down, it is countries such as the US, Canada, Australia, and Europe that are looking to scoop up immigrants to keep their population numbers stable and their economies growing. For Mauritius, this is an unprecedented situation: as a colony, it was an appendage of a larger British Empire and later could rely on much poorer countries to supply the labour for its economy. Now, none of these conditions exist anymore. In effect, when it comes to attracting immigrants and skills, it is competing with much larger European and North American states today. And possibly larger economies such as China, Japan and South Korea tomorrow. “We have the same needs as the US and Europe and these larger countries are much more interesting than we are. Our business and political leaders have to realize that there are more opportunities abroad today. So they need to provide more opportunities and a decent salary to compete,” says Dinan.

If Mauritius Inc. fails to retain Mauritians themselves, it’s unlikely that foreigners would choose Mauritius over bigger, more developed states offering much more. Particularly, when like Mauritius, those states are also becoming more dependent on the same shrinking pool of immigrants. “Mauritius ranks very poorly when it comes to the treatment of foreign workers and is just not attractive enough to young professionals. We cannot just think we can do what we did in the past,” argues Ancharaz. In short, if Mauritian business expects that just the government making immigration easier will solve its problems of attracting skills without itself having to offer more, it’s in for a major disappointment.

Renganaden Padayachy has urged the private sector to boost salaries to make itself more attractive and stem the brain drain problem.

Renganaden Padayachy has urged the private sector to boost salaries to make itself more attractive and stem the brain drain problem.

4. The political question

Aside from the economic and financial question, there is also a political angle that significantly complicates the immigration picture. The political history of Mauritius – and its continuing divide today – is essentially one of earlier waves of immigrants opposing later ones. To accommodate these divisions, the Mauritian political system has evolved into one which is dedicated to a delicate balancing act, ensuring adequate representation to each component of its population.

This is why after Independence, while Mauritius has been willing to temporarily let in immigrants to work, it has been more wary of opening the doors to long-term immigration on any significant scale. That is why Mauritius has not yet ratified refugee conventions at the UN and in the past has declined to take in refugees from anywhere. In the 1970s for example, Mauritius refused to take in refugees from African states and in 1975, similarly refused to take in any refugees from South Vietnam; even small numbers of skilled refugees it was feared would be enough to throw the delicate ethnic balance in Mauritian politics off. Just how susceptible the Mauritian political system can be to such considerations can be seen in how a handful of registered voters from Bangladesh have been made the target of a campaign accusing them of skewing the 2019 elections.

It’s hard to imagine that the Mauritian political system as it stands today will be flexible enough to accommodate a large influx of immigrants from abroad, nor how it will be able to break from the Mauritian historical tradition of older immigrants politically turning against newer ones, and introducing all new political divisions in an already ethnically and religiously divided polity. “We cannot just count on people from poorer countries coming to lift us up,” says Dinan. “Immigration is at best a temporary solution and there is a risk that such conflicts could erupt again.”

Immigration is no magic bullet that will save Mauritius Inc. For that to happen, Padayachy has a point. It will just have to start making itself attractive again, not just to foreign talent but more importantly, to the Mauritians who seem to be leaving it. And it will have to start by offering a fairer shake to its employees.

Publicité

Publicité

Les plus récents